|

|

Post by CSLR on Jul 18, 2014 11:29:20 GMT

This is a replacement for the original 'When signals were introduced' thread, which was hijacked by railtechnician.I assume your talking about the signals as used on the SSL, bakerloo, Piccadilly &c.? I guess that they can probably trace heritage to the CSLR, seeing as the traditional semaphore wouldn't be very good in that situation. Not really... All of the starting signals on the C&SLR were full-size semaphores, although the signal arms were shorter than those employed on surface lines. The two terminals even had overhead gantries in the roof of the station tunnels to carry the array of signals necessary for what would be more easily understood today as 'traffic' and 'shunting' operations. At intermediate stations, the semaphore signals were positioned at the headwall. There were illuminated signals in the confined space of the running tunnels, but these were noticably different to present day coloured light signalling. The original running tunnel signals consisted of a fixed light contained within a square box fronted by a plain convex lens. Coloured glass was mounted in an angled frame which was rotated 90 degrees around the outside of the box to change the aspect. Later C&SLR tunnel signals used the same principle, except that the coloured glass was held in a frame that moved up and down in front of the box - similar to the LER lines.

|

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Jul 18, 2014 17:25:57 GMT

I have often wondered why such a convoluted electro-pneumatic mechanical arrangement was used to display simple red and green lights in those old tunnel sticks when the required feeds could simply have illuminated two aspects as they do in the later colour light signals. As it seems so obvious to be able to light lamps without the air valve, motor, and mechanics one has to assume that there was more than just illuminating an aspect taking place! Electro-mechanical signalling was later, it was certainly not the case in the early days. Let me explain why, but first I will have to put this into context... Up until the opening of the C&SLR, there had only been some electric locomotive and tramcar experiments. There were no other electric railways and there was very little electricity anywhere. In fact the power station that the company built at Stockwell was probably the biggest in the world at the time of its opening - and it was small. In fact, there was not quite enough electricity to operate the railway efficiently (they quickly added more power) and certainly not enough to light the stations (they used gas). Across other railway companies, electricity was virtually unheard of. Signals everywhere in the world were illuminated by oil or gas, with some stations and trains supplementing this type of lighting with candles. When signals are illuminated by a flame, it is not feasible for a signalman to extinguish and reignite different coloured signal lights from a distance. It is far easier to move a coloured glass in front of a flame. That why there is a spectacle plate on the end of mechanical signal arms and that it is how all illuminated signals worked at the time that the C&SLR was opened for traffic. When the C&SLR needed coloured light signalling in its tunnels, it was either a case of using existing technology or trying to find a way of controlling a primitive electrical circuit from a mechanical signal frame of the type that was needed to control the interlocking. We can easily discuss alternatives with the benefit of both hindsight and subsequent developments, but this was unexplored territory in 1890 and the company do not seem to have had the time, the inclination or the money to try to develop a new system that may or may not have worked. It was far easier to stick as closely as possible to an off-the-shelf approved system. Thus the tunnel signals were adapted so that they were illuminated by a fixed electric light instead of a fixed oil light, but with redesigned spectacle plates so that they occupied a minimum amount of space. Other than that, the cable that controlled them only needed to be slipped inside some gas piping to get it round the curves in the tunnels. Result - pretty much a conventional mechanical system. |

|

rincew1nd

Administrator

Junior Under-wizzard of quiz

Posts: 10,286

|

Post by rincew1nd on Jul 24, 2014 19:02:43 GMT

How long did these kind of signals exist for, what brought about their demise as they seem so elegantly simple?

|

|

mrfs42

71E25683904T 172E6538094T

Big Hair Day

Posts: 5,922

|

Post by mrfs42 on Jul 24, 2014 19:47:24 GMT

I think kinematic envelope changes played a part.

|

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Jul 28, 2014 7:02:26 GMT

Following a number of PMs to me and a query in this thread, I will be posting a few more notes about the C&SLR signals. Before I do, I wish to scan some drawings of the first two types of signal that the company used. These should make my future comments a little clearer.

Please bear with me for a couple of days while I sort this out.

|

|

roythebus

Pleased to say the restoration of BEA coach MLL738 is as complete as it can be, now restoring MLL721

Posts: 1,275

|

Post by roythebus on Jul 30, 2014 16:42:58 GMT

I think kinematic envelope changes played a part. surely kinematic envelopes were found on the Post Office Railway??  |

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Jul 31, 2014 9:46:09 GMT

There is no doubt that some of the pioneering decisions made by the City & South London Railway influenced the structure of subsequent tube railways, and this undoubtedly included signalling decisions. This is not unusual, as the C&SLR itself would have taken note of what had gone before; however, it would have only had general railway practice to refer to as there were no other deep level systems at the time. Once it had opened, the C&SLR became a point of reference for other tube railways seeking to view good and bad practices. Having put the reasons for the initial choice of signals into context in my previous posts, I will now try to outline what I know in a little more detail. Let me begin with the first signals that were used in tube tunnels: These were specially designed and manufactured for the C&SLR by Dutton & Co. At the time that the railway opened, this was a new signalling business that had been incorporated just a year earlier. I am attaching the only illustration that I have ever found of a C&SLR 'box' signal of the Dutton type. The picture is taken from a thumbnail version of a drawing that accompanied a talk on the railway given by its engineer, J H Greathead in 1895. Unfortunately the quality of the image is poor as is has been greatly enlarged from a small section of drawing that Greathead was using to illustrate a different point. Please look at this image and at the following notes that have been derived from a description given by a signalling specialist who had the opportunity to examine the original signals.  The Dutton signals consisted of a narrow cast-iron box to hold the lamp with a stepped type lens of plain glass and with spectacle glasses arranged in two square frames at right angles to one another - these turned on a horizontal spindle. The whole arrangement, together with its balance lever, was bolted to the tunnel segments. These signals were originally lit by oil lamps with gas being tried later. This system of lighting proved problematic as the strong draughts in the tunnels extinguished the flames, so electric bulbs were subsequently introduced. I will discuss the electric versions further in the next post and will also include an illustration of the second type of box signal that incorporated spectacle glasses moving on a vertical plane. Any technical or operational comments regarding these signals would be most welcome. |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Jul 31, 2014 21:36:23 GMT

When were the current LUL conventional signals (Piccadilly, Met and Bakerloo etc) introduced? Just like the signal in my profile pic

That's what I'm trying to get at.

|

|

|

|

Post by southfieldschris on Aug 1, 2014 7:41:58 GMT

This is really interesting - looking forward to the next instalment...

|

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 1, 2014 10:36:20 GMT

When were the current LUL conventional signals (Piccadilly, Met and Bakerloo etc) introduced? Just like the signal in my profile pic That's what I'm trying to get at. If you are asking about the introduction of signals that used a separate source of illumination for each aspect (two or more lights)*, I can give you a date for the tube railways, but I am going to request forum members to allow me to do this in an unconventional way. I am trying to cover what happened chronologically and explain why thing happened the way that they did. This particular point comes a little further into the story and if I post the details now, we will go off at a tangent and it will raise other questions that I am hoping to cover anyway. If anyone wants the date now I will PM it to them, but I would ask members to bear with me and to let it appear in this thread in its proper place in this story. Should anyone be wondering why I am posting my comments in instalments: I am doing this to fit in with my time, to give members the opportunity to respond and to avoid overwhelming the forum with one gigantic post. * If this query concerns the specific type of signal that appears in your profile pic, the system-wide introduction of multiple light signals, route indicators or signals on the surface lines, I will have to leave the matter with others. |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Aug 1, 2014 12:52:34 GMT

It might be prudent at this point to remind readers the the original City & South Railway tunnels were of a smaller diameter that the current ones. I believe they were 10 ft 6 inches. This left much less room alongside the locomotive and carriages for anything that was bolted to the inside of the tunnels. Signals had to be physically as big as was reasonably possible so that the visible aspects were large enough, given the poor illuminant, for the drivers to see.

|

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 1, 2014 14:50:18 GMT

It might be prudent at this point to remind readers the the original City & South Railway tunnels were of a smaller diameter that the current ones. I believe they were 10 ft 6 inches. This left much less room alongside the locomotive and carriages for anything that was bolted to the inside of the tunnels. Signals had to be physically as big as was reasonably possible so that the visible aspects were large enough, given the poor illuminant, for the drivers to see. A very good point. As you say the tunnels from Elephant & Castle to Stockwell were 10' 6" while those between Elephant and King William Street were only 10' 2". The limited clearance between the rolling stock and the tunnel rings was made worse when the bogies swung the ends of each carriage into the outer edge of a curve and pushed the centre of a carriage into the inner edge. This was a real problem for the first batch of Ashbury carriages, which also had to contend with a single spring supporting two axles and trackwork that was not always level. That meant that theoretical gauging calculations were a work of fiction. Early carriages hit the running tunnels on curves and the brickwork of the station tunnels when entering or leaving a crossover - the latter problem eventually being solved by hacking a layer of brick off of the wall! From what I can establish, the lenses on the first signals were 6 inches in diameter. Poor illuminant was not so much a problem as no illuminant when the flame went out. But, that is where a moving spectacle has a distinct advantage. When there is no light, you can still see whether the signal is at clear or danger... ...and forget anything you were taught about treating an unilluminated signal as a sign for danger. All train crews carried matches for their cigarettes and pipes* and many seem to have treated the 'rule book' as another work of fiction. * Except the general manager T C Jenkin. He always carried cigars in the outer breast pocket of his jacket and would sometimes give one to a member of staff who had performed their duties particularly well. |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Aug 1, 2014 15:08:55 GMT

Poor illuminant was not so much a problem as no illuminant when the flame went out. But, that is where a moving spectacle has a distinct advantage. When there is no light, you can still see whether the signal is at clear or danger... From my reading I seem to recall that it was only after later modifications that headlights were provided on the locos. I interpret that as prior to the mod they did not have ant headlights at all. That would make seeing an extinguished signal extremely difficult. Added to which, I understand that there was really only one incident that could be called a train crash and that seems to be caused by nether of the two people in the loco simply not looking where they were going – nothing to look at in running tunnels between stations. Railway history generally indicates that there was quite a cavalier attitude to safety by some staff. I think that the in proceedings of the Institution of Railway Signal Engineers, Session 1941 p.40 T.S. Lascelles presented a paper entitled “Early Tube Railway Signalling”. If anyone has access to that record the document might throw (please excuse a pun) more light on the subject. |

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 2, 2014 9:52:57 GMT

From my reading I seem to recall that it was only after later modifications that headlights were provided on the locos. I interpret that as prior to the mod they did not have ant headlights at all. That would make seeing an extinguished signal extremely difficult. It is true that electric headlights were not fitted on the early locomotives, the locos did however carry an oil lamp at the front. Remember also that lighting on stations was by gas and the levels were very low, so there would not have been such a dramatic change in lighting levels as we might experience today when passing from a station into a dark running tunnel. In the past, I worked for many hours taking photographs in the tunnels leading to and from King William Street using a multiple flash technique over a long distance. The process required me to work in almost absolute darkness over a long length of tunnel. The only permanent illumination was a low level torch placed behind the camera which allowed me to find my way back to the start position without affecting the exposure: Click here to read the full details (I have recently been made aware that the accompanying photos, including the King William St section, disappeared when Imageshack went down. I am working with others to restore these pictures as soon as possible. In the meantime the description is still there) Once you read the above text, you will see that after each flash, the only illumination in the tunnel was the little torch which could have been 100 yards or more away from me (Note: 'yards'. The C&SLR did not do metric and neither do I). It is surprising how quickly one's eyes adjust, and just how much can be seen at a level of light that would have been much dimmer than an oil lamp focussed through a convex lens on the front of a locomotive. Let us take a look at this further: - The locomotive drivers and assistants would have been looking for signals and were required to know the position of every signal on the line. - When the railway opened, there was only one tunnel signal (a home) to watch near each station, although other tunnel signals were added later. Several drivers on the railway told me that because of the curves, gradients and slow speed, they could 'feel' exactly where they were between stations. And they were talking about a time after the line had been extended and when there was much more signalling. - All drivers had to take note of a list of signs that constituted a danger signal - I even remember this being one of the first things that I learned at LT training school. That list included 'no signal where one should be present'. - I know that drivers on the C&SLR sometimes intentionally bent the rules. I know that they passed signals at danger outside of permitted regulations and that they worked locomotives forward into sections that were already occupied, subsequently returning against the direction of travel without anything that would be accepted as wrong line working permission. (There is an old post somewhere that details this, perhaps someone could help to locate it). Regardless of this, staff would still have looked for and taken notice of a signal...until such time as they felt the need to 're-interpret' the rules. I therefore think that they would have seen a signal if they had wanted to, even if it was not illuminated. This reply is getting too long, so I will cover your other points in subsequent posts. |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Aug 2, 2014 11:24:54 GMT

Thank you for the link CSLR. It made interesting reading even though a lot was over my head. It seems a shame that so much got watered down at the end. It is a shame that none of the pictures were viewable. Just place holders. Others, in the past have obviously seen tham.

I think that I was looking at the boring, day to day life experiences of train crews. I am talking about crew operated trains here as I have never got myself involved with auto or one man trains. It most certainly true that any driver worth his (or her) salt should know where to look out, most importantly for signals, but also for other indications. I thought about 'Indications' for a long time but cannot think of an improvement. I am referring to all the little every day things you see round about the tunnel. Bolt holes, spare rails laid in the four foot, trip hazards (modern terminology) even some of the various little boxes that can be seen affixed to the tunnel wall. These can be useful reminders or even indicators of when to apply a bit of brake, shut off or apply power to the motors. All sort of things you see, but do not actually see. All these things a part of 'being a good driver'. The unusual will stick out like the proverbial sore thumb, even if you don't actually see it. You will just know that something is different.

So, yes. a signal that is out, or missing when the driver is expecting one should certainly be noticed. Its absence should leap out at the driver. But that is making the assumption that he is fully awake, not distracted by something or the other, being concerned about some unusual noise that might indicate that something is wrong with his locomotive. Signals should take priority. I was merely saying that drivers are human. The main line call the SPADs. Signals passed at danger. LT has had thousands of them. Low light, even if your eyes are accustomed to it, can create unexpected shadows and reflections. The fact that there was only apparently only one incident that could be called a crash on the C&SLR only goes to show just how good their drivers were.

|

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 2, 2014 21:42:20 GMT

Two more points to cover here, both of which are connected: I think that the in proceedings of the Institution of Railway Signal Engineers, Session 1941 p.40 T.S. Lascelles presented a paper entitled “Early Tube Railway Signalling”. If anyone has access to that record the document might throw (please excuse a pun) more light on the subject. Lascelles worked for an interlocking signal company for 45 years and held various positions in IRSE, so he knew the subject. I have the text of 'Early Tube Railway Signalling' beside me, and it is Lascelles description of a Dutton signal that I paraphrased in a previous post. As far as I know, this piece was only written to fill some space in the Institution's annual publication as no papers were submitted to it in 1941 due to the war; so it is a bit of a fluke that it exists at all. I understand that there was really only one incident that could be called a train crash and that seems to be caused by nether of the two people in the loco simply not looking where they were going – nothing to look at in running tunnels between stations. Railway history generally indicates that there was quite a cavalier attitude to safety by some staff. This 'one incident' quote is actually an opinion by Lascelles and he based his view solely on the official accident report. The report had been drawn to his attention by a couple of railway inspectors that he spoke to while writing another short paper that was eventually published as 'The City & South London Railway'. The quote in question says: 'The City & South London Railway was remarkably free from accidents. Only one "train accident", properly so called, was the subject of an official enquiry...' The last sentence - which refers to a collision between London Bridge and Bank - is true, but I would challenge the preceding statement. While the City & South London actually had several train accidents (and a few other accidents not involving trains), it appears to have been rather good at keeping the railway inspectorate away from its doors. It also did quite a few unapproved things and made several unauthorised alterations without telling the inspectors, but that is another story. Two trains unintentionally entering the same section is a problem and collisions from the rear are almost always caused when the integrity of a block section is breached. The prevention of such incidents is one of the primary reasons why signals exist. But, two trains in a section seems to have been a relatively common occurrence on the C&SLR, more often than not caused by rule bending rather than bad driving. Rather strangely, during the London Bridge/Bank collision enquiry, the C&SLR actually admitted an incident where there had been three trains in one section at the same time a few weeks previously!!! This admission was very unusual and most incidents were never reported simply because they were conveniently forgotten soon after they happened. The reason that the company got away with so much was that the speeds were low and the trains could usually be stopped before impact. Also, passengers could not see what was happening in the tunnels (so they did not report anything) and staff could normally sort things out without any delay to the service. Management opinion seems to have been, keep the line running and we will not ask awkward questions on how it is done. If you would like to look at this in more detail, see 'Life Underground in 1920. A supplement to Underground News no.555, March 2008'. The section between pp .235-241 gives examples of seemingly impossible C&SLR timetable moves together with notes on some of the creative ways that staff achieved these. There is more analysis on the ingenuity of staff when moving trains on the C&SLR on pp.58-61 of 'Underground News no.566, February 2009' |

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 7, 2014 9:30:00 GMT

I am aware that there is some additional information that I said I would add to this post.

In order to clarify what happened and to suggest why things developed the way that they did, it is necessary to refer to an illustration of an Evans O'Donnell tunnel signal. The drawings that I have are full size on rather old tracing paper - of the type that was used for blueprint/dyline printing - and the lines are very thin. It has not been possible to produce a scan that is readable when reduced to the size required for inclusion in a post.

I am currently re-drawing the illustration in a style that I can put on the forum. It is on its way...

... to be continued

|

|

|

|

Post by domh245 on Aug 10, 2014 19:40:11 GMT

Just to add some further info, just seen an advert for "The Tube" on london live, and they had a snippet from the episode where the guy was doing maintenance of the signals on the met. He said "These signals were built about 70 years ago" which would place the signal as being built about 1940. And to clarify, the signal he was working on was a double aspect with attached repeater, I'm not sure which particular one.

|

|

|

|

Post by nidave on Aug 13, 2014 10:16:48 GMT

This is really interesting stuff. Thanks for posting and keep it coming  |

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 14, 2014 21:31:18 GMT

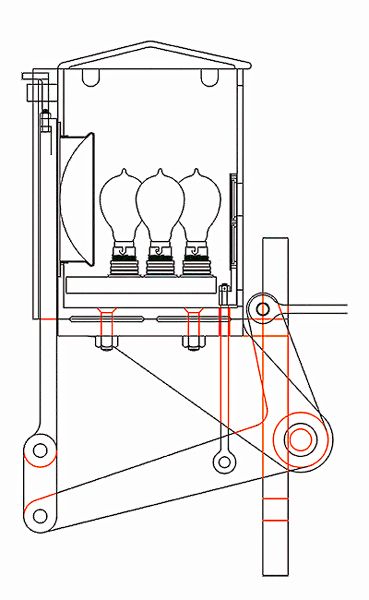

When the C&SLR set out its initial plan in 1888 to abandon cable haulage in favour of electrical operation, it proposed electric lighting for the stations and the trains, together with 'two electric lamps' for each signal. The signals were to be a single light fronted by a coloured spectacle plate with the second lamp being available as a simple back-up in case the first one failed. By the time that the company got round to installing the signalling, it was obvious that it needed as much current as possible for traction, so the electric lighting for the stations and signals was dropped. Electric lamps were retained for the carriages, but these were inefficient, with oil lamps in the carriages being the only reliable source of light when the electric lamps dimmed under load. At the time that the line opened, mechanical railway signalling was the standard, so that is what the company purchased. The Dutton tunnel signal was the only thing that appears to have been specially designed. On paper, it might have looked like a novel space saving design, but in practice it was probably not the best of ideas. With two frames holding coloured spectacle glasses at right angles to each other and rotating on a horizontal spindle, there were times when one of the frames would have moved into the space between the side of the signal and the tunnel segment. During this turn, there would have been extremely limited clearance between the upper corner of the frame and the wall, which could easily have caused the mechanism to break or jam. In case of such a problem, the limited space behind the signal and the difficulty accessing it would have made maintenance difficult. The subsequent introduction of spectacles moving on a vertical axis seems to have been a sensible way to overcome these issues. The introduction of a vertical motion was also more in keeping with the signals on other railways and it appears to me to have the added advantage of offering a better fail-safe as, in the event of a loss of counterbalance, a vertical motion signal will fall down into the danger position. Using the same scenario, I cannot see how a Dutton horizontal motion signal could 'fall' into a danger position - sideways! One of the difficulties encountered by the C&SLR in controlling its mechanical signalling, was that of a signal wire breaking inside the iron (gas-type) pipes that were used to guide these cables through the tunnels. This would certainly have been a difficult and disruptive repair job to conduct during traffic hours. Although the company did not have any spare electrical capacity when it started, it did have an abundant supply of hydraulic power that it used for the lifts. The hydraulic flow and return pipes ran the full length of the line through the running tunnels and it has always amazed me that the C&SLR did not apply its usual ingenuity by attempting to play around with this. Had it done so, we may have moved into an era of hydro-mechanical signalling and from there to electro-hydro-mechanical signals...but they did not do that, and sadly there is no evidence that they ever even thought about it. Electric bulbs were certainly used in the C&SLR signals from 1894, at the same time that the company introduced an electro-mechanical 'repeater' (a proving circuit that linked a signal with the signal cabin that controlled it). The signals, of course, were still a single light shining through a movable coloured lens. A few years later, in 1898, the Waterloo and City Railway opened with electric tunnel signals using a moving spectacle plate inside the signal casing. The Evans O'Donnell tunnel signal appeared on the C&SLR in 1900 with the opening of the extension to Moorgate Street and it subsequently became the standard on the line, although the Duttons remained in use. The illustration below shows a cut-away side elevation of an Evans O'Donnell signal.  I have redrawn this from a full-size plan, omitting some minor details (such as rubber stops and hinges) for clarity at this smaller scale. The spectacle plate is shown in the down (danger) position. Red lines are used to indicate hidden detail. Four electric bulbs are housed within the signal and are laid out in a diamond configuration with one being hidden from view in this elevation. There is a back light that is operated by a small sliding spectacle plate that moves behind a hole in the signal casing. This was the subject of an observation by the inspecting officer who visited the line prior to the opening of the Angel extension. He pointed out that the back light shone green when the main signal was at danger and that this could be confusing to drivers performing shunting moves. At his request, these glasses were subsequently changed to crimson. At this point the signalling on other underground railways comes into the story... Is anyone still awake? |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Aug 14, 2014 21:43:57 GMT

Very much so. And eagerly, in fact  |

|

|

|

Post by brigham on Aug 15, 2014 1:37:07 GMT

Was the 'clear' (signal off) aspect green, as well as the back-light? That would be a very unusual combination. Green back-lights were used in the early days of railway signalling, when the 'clear' aspect was white. They were changed to the present-day white when 'green for go' was introduced.

|

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on Aug 15, 2014 9:40:46 GMT

Can I thank you for this very interesting series I am looking forward to the next installment. Perhaps when it is completed it could be put together as one, including pertaining comments, so that it is easier to read in the future in one go.

Thanks again.

John

|

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 15, 2014 11:42:52 GMT

Was the 'clear' (signal off) aspect green, as well as the back-light? That would be a very unusual combination. Green back-lights were used in the early days of railway signalling, when the 'clear' aspect was white. They were changed to the present-day white when 'green for go' was introduced. Good point and something that has caused me a lot of confusion in the past. One of my biggest regrets is that I did not seize the opportunity to sit down and talk to Lascelles on these matters. He was a real expert on C&SLR signals, but there was so much that he did not write down and a lot of points that he mentioned without expanding the details. I hope that others with an interest in history might learn from this and will take every opportunity to speak to those who know their subject before it is too late. But I digress. The simple answer to this question is. From all available evidence, the company had standard red and green aspects to its signals. The matter of the green light relates purely to the back light on the tunnel signals; specifically Evans O'Donnell signals. Even the 'repeater' bulbs that indicated the aspect in the signal cabin (from 1894 onwards) showed standard red and green lights. There are several references elsewhere to the green back light being used from the opening of the line, and I am guilty of having mentioned this in the past based on information that was given to me. I must say that I am not sure now that this was the case. Because there are no complete drawings of a Dutton tunnel signal available to me, I do not know what the back light arrangement was, or even if they had a back light. We must remember that the Dutton signals were small and operated by a horizontal rotation of the aspects. I cannot imagine how the mechanics of a back light would work within this design. The Dutton tunnel signal was a special design for use in a specific location by a railway that did not undertake the type of traffic movement in which a back light would be advantageous. My current opinion is that while there was certainly a back light on the Evans O'Donnell signals, there may not have been a back light on the Dutton signals. But that is only an opinion.Evans O'Donnell signals were installed on the Clapham Common and Moorgate Street extensions when they opened in 1900 and on the Angel extension of 1901. The undated Evans O'Donnell drawing - from which I produced the illustration in my last post - shows the upper back light glass as 'Green (danger)' and the lower glass as 'white'. The front glasses are not labelled. The words 'Green (danger)' have subsequently been crossed out and replaced by the word 'Crimson' in a different handwriting. There is no reference to the tunnel signals in the inspecting officers' reports on the Clapham Common or Moorgate Street extension. It was not until the inspection of the Angel extension in November 1901 that Col Yorke (the inspecting officer) commented, "I noticed that the back lights of all the signals on this line are green when the front lights are showing the danger signal viz red - there is an objection to this arrangement inasmuch as a green light (even though small) might mislead a driver during a shunting movement and induce him to proceed in the wrong direction farther than intended. I do not know how this system of lights originated but I suggest that the company should consider the desirability of conforming to the usual practice as defined in Board of Trade requirements number 4." The term 'all the signals on this line' probably refers to the signals on the line that was being inspected (Moorgate Street to Angel), as the inspector would almost certainly have used the term 'railway' when referring to the C&SLR as a whole. This does not mean that the other signals did not have back lights. The three extensions that I have mentioned were all built and equipped around the same time and I would therefore think that the design of the Evans O'Donnell signal was unchanged during this period. If that was the case, then green (danger) back lights were used from 25 February 1900 (when the Moorgate Street extension opened) until some time after 27 November 1901 (when Col Yorke submitted his report). It is possible that the arrangement existed earlier if the Dutton signals had the same arrangement, but I have no way of confirming that. I tried to make this reply short, but I appear to have been unsuccessful. |

|

|

|

Post by programmes1 on Aug 15, 2014 12:39:40 GMT

The paper Early Tube railway signalling is on page 40 link |

|

|

|

Post by programmes1 on Aug 15, 2014 12:57:32 GMT

Was the 'clear' (signal off) aspect green, as well as the back-light? That would be a very unusual combination. Green back-lights were used in the early days of railway signalling, when the 'clear' aspect was white. They were changed to the present-day white when 'green for go' was introduced. One of my biggest regrets is that I did not seize the opportunity to sit down and talk to Lascelles on these matters. He was a real expert on C&SLR signals, but there was so much that he did not write down and a lot of points that he mentioned without expanding the details. CSLR as TS Lascelles died on the 17/2/60 as I am sure you know I did not think you were of that vintage? |

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 15, 2014 13:32:49 GMT

I did not think you were of that vintage? I became interested in the C&SLR after trying to resolve two apparently conflicting statements in Lascelles booklet on the railway. My quest began just over a year before Lascelles died and I finally found the solution to that problem 16 years later. |

|

|

|

Post by tjw on Aug 15, 2014 14:51:29 GMT

Hmm this Dutton Rotating signal sounds very much like a LBSCR shunting signal otherwise known as a dolly / tommy dod / dummy image here, www.flickr.com/photos/31514768@N05/3983596994/colour images can be found by scrolling down this page, www.bluebell-railway.co.uk/bluebell/ssb.htmlThe Bluebell Railway have at least 2, one of which was in the museum and another in store. I am told they are not very reliable and so the one in the photograph above has been taken out and replaced with an SR design. |

|

|

|

Post by programmes1 on Aug 15, 2014 15:00:38 GMT

I did not think you were of that vintage? I became interested in the C&SLR after trying to resolve two apparently conflicting statements in Lascelles booklet on the railway. My quest began just over a year before Lascelles died and I finally found the solution to that problem 16 years later. In your photo you don't look old so well done. |

|

|

|

Post by CSLR on Aug 15, 2014 16:43:44 GMT

Hmm this Dutton Rotating signal sounds very much like a LBSCR shunting signal otherwise known as a dolly / tommy dod / dummy That is an interesting looking signal. From what I can make out, it appears that the whole signal rotates. In the case of the Duttons, the light remained stationary while the coloured glasses moved around the signal housing. The Dutton signals were also considerably smaller and of a lighter construction. I would imagine that an LBSCR shunting signal bolted to the side of a tube tunnel would take the side out of a locomotive. |

|